The wild weather fluctuations wrought by climate change are stressing out our plants. Our resident gardening expert, Professor Geoff Dixon, explains how.

Pests and diseases are familiar causes of plant damage and loss. Less familiar, but becoming more frequent, are stresses resulting from environmental causes.

These are termed abiotic stresses because no living organism is involved. This means there are no visible signs of pests or pathogens. Diagnosis and treatment are, therefore, less straightforward. These causes are a result of interactions between the plant genotype and the prevailing or changing environment.

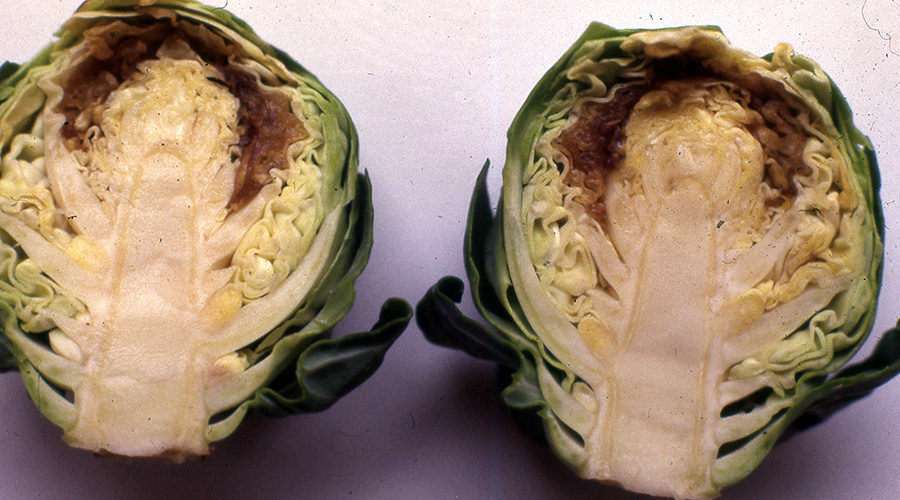

Damage may only become apparent after harvesting and at the point of consumer use. A typical example of this is internal browning or breakdown of Brussels sprouts. Larger sprouts are more susceptible to stress, with dense leaf packing in the bud, particularly in early and midseason cultivars.

The internal browning of Brussels sprouts is a consequence of plant stress.

A suggested cause is water condensing within the bud, which restricts calcium transport and leads to marginal leaf necrosis (death). This resembles the exudation, or perspiration, of water from leaf edges when growing plants absorb excessive water, flooding the vascular systems following very heavy rainfall and hot weather.

Moisture damage

Oedema is another moisture-induced disorder. Symptoms include unattractive wart-like swellings coalescing on leaves and stems, particularly on Brussels sprouts, cabbages, and cauliflowers. These may rupture, becoming corky with a yellowish or brownish appearance.

Moisture-induced damage to cabbage leaves.

These symptoms result from high soil moisture content and high relative humidity associated with hot days and cool nights. Both internal browning and oedema can be minimised by improving soil structure, encouraging rapid drainage by deep cultivation or growing plants on raised beds.

Improving soil structure is becoming an important way to control salt accumulation. Soil structure can be badly damaged by flooding that brings in polluted water. In subsequent vegetable and fruit crops, plant water uptake, nutrient use efficiency, and photosynthesis are all impaired. The effects are seen in poor germination, burnt leaf margin, stunting, and wilting. This damage will be particularly severe with highly organic soils.

Salt accumulation in onion crops. Improving soil structure is one way of addressing this problem.

Abiotic disorders are becoming more common in commercial crops and this is likely to be reflected in gardens and allotments. That is an effect of climatic change, with generally hotter and wetter conditions interspersed by droughts and freezing events.

As a result, plant growth is erratic and exhibits abiotic disorders. Plant breeders, especially in Asia, are actively seeking genetic solutions that will create crops capable of withstanding erratic environments. In parallel,the agro-chemical industry is producing environmentally sustainable compounds and biostimulants to help combat these problems.

>> How else has climate change changed the way our gardens grow, and what can be done to alleviate its effects? Geoff Dixon explored this issue further.

Professor Geoff Dixon is author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

How do green spaces, gardens as well as fruit and vegetables impact our health and wellbeing? Professor Geoff Dixon tells us more.

‘We are what we eat’ is an aphorism that is becoming much better understood both by the general public and by healthcare professionals. Similarly, ‘we are where we live’ is gaining greater appreciation. Both these pithy observations underline the social and economic importance of horticulture and the allied art of gardening.

An exuberant display of flowers – what can be better for the soul?

Few things stimulate the human spirit more than a fine, colourful display of well grown and presented flowers. Seeing and working with green and colourful plants is increasingly recognised for its psychological power, reducing stress and increasing wellbeing. In our increasingly urbanised society, with myriads of high-rise housing blocks, the provision of well-tended parks and gardens is not a luxury – it is essential.

Hospital patients recover more quickly when they can see and sit in green spaces. Equally, providing access to gardens and gardening for schools should be a vital part of the children’s environment. They gain an understanding of biological mechanisms and the equally important need for conserving biodiversity and controlling the rate of climate change.

The recently published National Food Strategy emphasised the importance of fruit and vegetables as a major part of our diets. Both fruit and vegetables provide essential vitamins, nutrients and fibres which consumed over time diminish the incidence of cancers, coronary, strokes and digestive diseases.

Apricots are high in catechins.

Eating varying types of fruit and vegetables increases their value – apricots, for example, are high in catechins which are potent anti-inflammatory agents. Members of the brassica (cabbage) family are exceptionally valuable for mitigating diseases of ‘modern society’. All contain glucosynolates, which evolved as means for combating pest and pathogen attacks and co-incidentally provide similar services for humans. Watercress – an aquatic brassica – is rich in vitamins A, C and E, plus folate, calcium and iron. Its high water content means portions consumed fresh or as soups are low in calories.

Watercress – an aquatic brassica boasts numerous health benefits.

These messages and facts are now being recognised both publicly and politically, and not before time. For the past 50 years the universal panaceas have been pharmaceutical drugs. In moderation, these have been of immense value. Use to excess is both counterproductive and needlessly expensive health-wise and financially.

Returning to Grandma’s advice, ‘an apple a day keeps the doctor away’, supports both individual and planetary good health.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

Crop rotation, seaweed extracts, lime, and a range of organic materials can all improve soil health and crop yields. Professor Geoff Dixon shows you several ways to improve your soil.

Rapidly rising costs of living are affecting all aspects of life. Increasing costs of fertilisers are affecting food production, both commercially and in gardens and allotments.

Wholesale prices of fertilisers have jumped four-fold from £250 to £1,000 per tonne within six months. All forms of garden fertilisers are now much more expensive. Crops, especially vegetables, only thrive if provided with adequate nutrition (see nitrogen-deficient lettuce below). Consequently, fertiliser use must become more efficient.

Nitrogen deficiency in lettuce.

Healthy, fertile soils achieved through good management are key to this process. That ensures roots can take up the nutrients needed in quantities that result in balanced, healthy growth.

Soil pH is a major regulator of nutrient availability for roots. Between pH 6.5 to 7.5, the macro nutrients, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium are fully available for root uptake. Below and above these values, nutrient absorption becomes less efficient.

>> How much soil cultivation do you need for your vegetables? Find out more in Prof Dixon's blog on cultivation.

As a result, soluble nutrients are wasted and washed by rainfall below the root zones. Acidic soils can be improved by liming in the autumn. Sources of lime derived from crushed limestone require up to six months to cause changes in soil pH values. Lime should be used in ornamental gardens with caution as it can result in micronutrient deficiencies.

Iron deficiency in wisteria.

Soil health and fertility are greatly increased by adding organic materials such as farmyard manure and well-made composts. Increasing soil carbon content helps mitigate climate change while raising fertiliser use efficiencies.

Beneficial soil biological life such as earthworms, insects, benign bacteria and fungi are greatly encouraged when you increase soil humus content. Using crop rotations, which include legumes, raises natural levels of soil nitrogen. This is a result of legumes’ symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria.

Leafy vegetables such as brassicas require large amounts of nitrogen and, hence, should follow legumes in a rotation. Avoiding soil compaction encourages adequate aeration, benefiting root respiration and providing oxygen for other organisms.

Organic materials are of great value in ornamental gardens when applied as top dressings in late autumn or early spring. This provides two benefits: a slow release of nutrients into the root zones as decomposition occurs, and prevention of weed growth.

Inorganic fertiliser use can be further minimised by using proprietary seaweed extracts. These contain macro- and micro-nutrients plus several natural biostimulant compounds that aid healthy ornamental plant growth and flowering (illustration no 3 rose Frűhlingsgold).

Rose frűhlingsgold

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science.

How do flowers use fragrance to attract pollinators, and how do pollution and climate change hamper pollination? Professor Geoff Dixon tells us more.

‘Fragrance is the music of flowers’, said Eleanour Sophy Sinclair Rohde, an eminent mid 20th century horticulturist. But they are much more than that. Scents have fundamental biological purposes. Evolution has refined them as means for attracting pollinators and perpetuating the particular plant species emitting these scents.

There are complex biological networks connecting the scent producers and attracted pollinators within the prevailing environment. Plants flowering early in the year are generalist attractors. By late spring and early summer, scents attract more specialist pollinators as shown by studies of alpines growing in the USA Rocky Mountains. This is because there is a bigger diversity of pollinator activity as seasons advance. Scents are mixtures of volatile organic compounds with a prevalence of monoterpenes.

Environmental factors will affect scent emission. Natural drought, for example, changes flower development and reduces the volumes and intensity of scent production. The effectiveness of pollinating insects, such as bees, moths, hoverflies and butterflies is reduced by aerial pollution.

Pheasant’s eye daffodils (Narcissus recurvus).

Studies showed there were 70% fewer pollinators in fields affected by diesel fumes, resulting in lower seed production. Pollinating insects do not find the flowers because nitrogenous oxides and ozone change the composition of scent molecules.

Extensive studies of changes in flowering dates show that climate change can severely damage scent–pollinator ecologies. Over the past 30 years, blooming of spring flowers has advanced by at least four weeks. Earlier flowering disrupts the evolved natural synchrony between scent emitters and insect activity and their breeding cycles. In turn that breaks the reproductive cycles of early flowering wild herbs, shrubs and trees, eventually leading to their extinction.

The lilac bush, known for its evocative scent.

Heaven scent

Scents provide powerful mental and physical benefits for humankind. Pleasures are particularly valuable for those with disabilities especially those with impaired vision. Even modest gardens can provide scented pleasures.

Bulbs such as Pheasant’s eye daffodils (Narcissus recurvus) (illustration no 1), which flower in mid to late-spring, and lilacs (illustration no 2) are very rewarding scent sources.

Sweetly perfumed annuals such as mignonette, night-scented stocks, candytuft and sweet peas (illustration no 3) are easily grown from garden centre modules, providing pleasures until the first frosts.

Sweet peas are easily grown from garden centre modules.

Roses are, of course, the doyenne of garden scents. Currently, Harlow Carr’s scented garden, near Harrogate, highlights the cultivars Gertrude Jekyll, Lady Emma Hamilton and Saint Cecilia as particularly effective sources of perfume. For larger gardens, lime or linden trees (Tilia spp) form profuse greenish-white blossoms in mid-season, laden with scents that bees adore.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

How much soil cultivation do you need for your vegetables? Professor Geoff Dixon explains all.

Cultivating soil is as old as horticulture itself. Basically, three processes have evolved over time. Primary cultivation involves inversion which buries weeds, adds organic matter and breaks up the soil profile, encouraging aeration and avoiding waterlogging.

Secondary cultivation prepares a fine tilth as a bed for sowing small seeded crops such as carrots or beetroot. In the growing season, tertiary cultivation maintains weed control, preventing competition for resources (illustration no. 1) such as light, nutrients and water while discouraging pest and disease damage.

Lettuce and seed competition

The onset of rapid climate change encouraged by industrialisation has focused attention on preventing the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Ploughing disturbs the soil profile and accelerates the loss of carbon dioxide from soil.

It is also an energy intensive process. Consequently, many broad acre agricultural crops such as cereals, oilseed rape and sugar beet are now drilled directly without previous primary cultivation. An added advantage is that stubble from previous crops remains in situ over winter, offering food sources for birds. The disadvantages of direct drilling are: increased likelihood of soil waterlogging and reduced opportunities for building organic fertility by adding farmyard manure or well-made composts.

Overall, primary and secondary cultivation benefit vegetable growing. The areas of land involved are far smaller and the crops are grown very intensively. Vegetables require high fertility, weed-free soil, good drainage and minimal accumulation of soil-borne pests and diseases.

Frost action breaking down soil clods

Digging increases each of these benefits and provides healthy physical exercise and mental stimulation. Frost action on well-dug soil breaks down the clods (illustration no. 2). Ultimately, fine seed beds are produced by secondary cultivation (illustration no. 3), which encourage rapid germination and even growth of root and salad crops.

Tertiary cultivation to prevent weed competition is also of paramount importance for vegetable crops. Competition in their early growth stages weakens the quality of root and leafy vegetables, destroying much of their dietary value. Regular hoeing and hand removal of weeds are necessities in the vegetable garden.

Raking down soil producing a fine tilth

Ornamental and fruit gardens similarly benefit from tertiary cultivation. Weeds not only provide competition but are also unsightly, destroying the visual image and psychological satisfaction of these areas.

Lightly forking over these areas in spring and autumn encourages water percolation and root aeration. Once established, ornamental herbaceous perennials and soft and top fruit areas benefit greatly from the addition of organic top dressings. Over several seasons these will augment fertility and nutrient availability.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

Gardens in December should, provided the weather allows, be hives of activity and interest. Many trees and shrubs, especially Roseaceous types, offer food supplies especially for migrating birds.

Cotoneaster (see image below) provides copious fruit for migrating redwings and waxwings as well as resident blackbirds. This is a widely spread genus, coming from Asia, Europe and northern Africa.

Cultivated as a hedge, it forms thick, dense, semi-evergreen growth that soaks up air pollution. In late spring, its white flowers are nectar plants for brimstone and red admiral butterflies and larval food for moths. Children and pets, however, should be guided away from the attractive red berries.

Cotonester franchetti | Image credit: Professor Geoff Dixon.

Medlars (Mespilus germanica) offer the last fruit harvest of the season (see image below). These small trees produce hard, round, brownish fruit that require frosting to encourage softening (bletting).

Its soft fruit can be scooped out and eaten raw and the taste is not dissimilar to dates. Alternatively, medlar fruit can be baked or roasted and, when turned into jams and jellies, they are delicious, especially spread on warm scones.

Like most rosaceous fruit, medlars are nutritionally very rich in amino acids, tannins, carotene, vitamins C and B and several beneficial minerals. As rich sources of antioxidants medlars also help reduce the risks of atherosclerosis and diabetes.

Medlar fruit (Mespilus germanica) can be turned into jams and jellies | Image credit: Professor Geoff Dixon.

Garden work continues through December. It is a time for removing dead leaves and stems from herbaceous perennials, lightly forking through the top soil and adding granular fertilisers with high potassium and phosphate content.

Top fruit trees gain from winter pruning, which opens out their structure, allowing air circulation when fully laden with leaves, flowers and fruit. Fertiliser will feed and encourage fresh root formation as spring progresses.

The vegetable garden is best served by digging and incorporating farm yard manure or well-rotted compost, which adds fertility and encourages worm populations. The process of digging is also a highly beneficial exercise for the gardener (see illustration no 3).

Turning the soil isn’t only good for your garden - it boosts your wellbeing | Image credit: Professor Geoff Dixon.

Developing a rhythm with this task supports healthy blood circulation and, psychologically, provides huge mental satisfaction in seeing a weedy plot transformed into rows of well-turned bare earth.

When the weather turns wet, windy and wintery it provides opportunities for cleaning, oiling and sharpening tools, inspecting stored fruit and the roots of dahlias kept in frost-proof conditions.

Finally, there is always the very relaxing and pleasant task of reading through seed and plant catalogues and planning what may be grown in the coming seasons.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

How has climate change changed the way our gardens grow and what can be done to alleviate its effects? Professor Geoff Dixon tells us more.

Climate has changed on Earth ever since it solidified and organic life first emerged. Indeed, the first photosynthesising microbes changed the atmosphere from carbon dioxide rich to oxygen rich over millions of years. What we now face is very rapid changes brought about by a single organism, mankind, through industrialisation.

The effects of change are very evident in gardens. Over a generation, leaf bud breaking and flowering by early spring bulbs, herbaceous plants, shrubs and trees has advanced by at least four weeks (see main image of Cyclamen hederifolium).

Latter spring displays have advanced by at least two weeks. This is caused by milder, wetter winter weather, encouraging growth. The danger lies in the increasing frequency of short sharp spells of severe frost and snow. These kill off precocious flowers and leaves which trees especially cannot replace.

Desiccated, cracked soil.

Increasingly, the summer climate is becoming hotter and drier. Since the Millennium there has been a succession of hot droughts. These seriously limit scope for growing vegetables, fruit and ornamentals unless irrigation is regularly available. Drought also damages soil structure especially where there is a high clay content by causing cracking and the loss of plant cover (see image of desiccated, cracked soil above).

Cracking disrupts and destroys the root systems of trees and shrubs in particular. The effects of root damage may not become evident until these plants die in the following years.

Climate change is apparently advantageous for microbes. Detailed surveys show that fungal life cycles are speeding up, increasing the opportunities for diseases to cause damage. Even normally quite resilient crops such as quince are being invaded during milder, damper autumns (See image of brown rot on quince fruit below). Throughout gardens, the range and aggressiveness of pests and disease is increasing.

Brown rot (Monilia laxa) on quince fruit.

However, each individual garden or allotment, no matter its size, can contribute to reducing the rate of climate change. Simple actions include the removal of hard landscaping, and planting trees and shrubs reduces carbon emissions.

Using electric-powered tools and machinery in place of petrol or diesel has similar advantages. Tumbling down parts of a garden into native flora, and perhaps encouraging rarer plants such as wild orchids or fritillarias, mitigates climate change. Such areas may also form habitats for hedgehogs or slow worms, increase populations of bees, butterflies and moths and encourage bird life.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

All images from Professor Geoff Dixon.

Lilies provide gloriously beautiful and well scented flowering border plants. Choose flowering size bulbs in the garden centre or from a catalogue. Grow these through the winter potted in a general garden compost placed in an unheated greenhouse or cold frame. By March or early-April, substantial green shoots will have formed from the bulbs and they can be transplanted into the garden.

Lilies need a sunny border and very fertile soil to encourage vigorous root growth capable of supporting the flowering spike and ancillary bulbs as they are initiated. This produces magnificent flowers and an increasing colony of bulbs that will spread and become established over future seasons.

Lilium longiflorum, often called the Easter lily | Image credit: Professor Geoff Dixon.

Regular watering and feeding with nutrients are needed, especially potassium, which encourages root and shoot growth. Stake the flower spike as it grows, giving support for the flowers because they are heavy when fully open and easily damaged by winds.

Rewards come in mid-summer with magnificent colourful flowers and wonderful perfumes on warm evenings. Apart from severe winters, lilies are hardy garden plants unless they are from groups specified as tender and requiring protection. In the autumn, simply cut down the flowering spike and remove any fallen foliage.

Buds developed on lily scales after culturing | Image credit: Professor Geoff Dixon.

The Lilium genus has about 100 species originating worldwide mainly from north temperate areas of Europe, Asia and America. The colour range includes white, yellow, orange, pink, red and purple. Plant breeders in The Netherlands, Japan and North America have produced a huge range of multi-coloured hybrids.

Taxonomically, Lilium is divided into divisions, of which the Turk’s Caps, Martagons and American hybrids are popular. The most destructive pest is the scarlet lily beetle (Lilioceris lilii) which devours foliage, flowers and bulbs. The first signs of trouble are shot holes in the foliage. Picking off beetles and larvae is an effective means of dealing with low-level infestations.

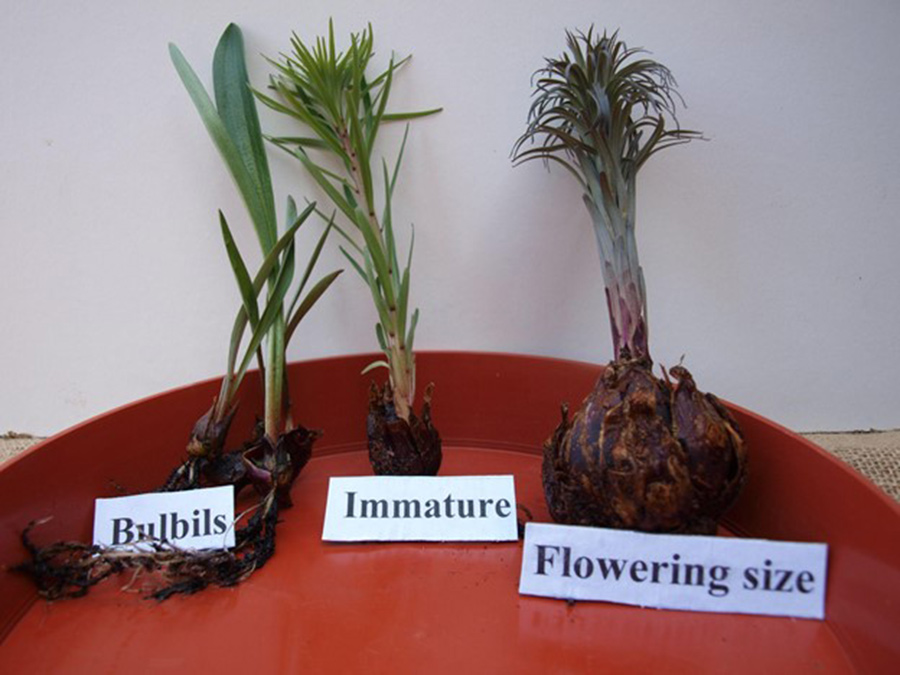

Comparison of lily bulbils growing from scale leaves, immature bulb and flowering size bulb | Image credit: Professor Geoff Dixon.

Asexual propagation is a simple and enjoyable occupation. Divide a good-sized bulb into its scales. Choose healthy scales from the outer rings and place these in a plastic box containing damp kitchen paper and place in an airing cupboard. After about 10-12 weeks, small bulbils will have formed on each scale.

Select the boldest mother scales and bulbils and plant in a tray of seedling compost and grow in the greenhouse. After two or three months the most vigorous young plants can be potted individually. Eventually these are planted in the garden and will develop into flowering size bulbs after two or three years.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

Main image: Pea crop | Image credit: Geoff Dixon

Peas are a very rewarding garden crop. Husbandry is very straightforward, producing nutritious yields and encouraging soil health by building nitrogen reserves for future crops.

Rotations usually sequence cabbages and other nitrogen-demanding crops after peas. This is a sustainable way to use the organic nitrogen reserves left by pea roots resulting from their mutually beneficial association with benign bacteria. These microbes capture atmospheric nitrogen, producing ammonia, nitrites and nitrates in a sequence of natural steps.

Peas originated in the Mediterranean. They were cultivated continuously by ancient civilisations and through medieval times, and are now the seventh most popular vegetable.

Illustration 1: Pea seeds | Image credit: Geoff Dixon

In bygone centuries, peas provided a protein source for the general population as cooked meals of pea soup and pease pudding helped keep famine at bay before the introduction of potatoes. In the 18th century, French gardeners working for the aristocracy produced fresh peas using raised and protected beds of fermenting animal manure. The composting processes produced heat and released carbon dioxide, stimulating rapid growth.

Generally, however, eating fresh peas only gained popularity in the 20th century as canned and then quick-frozen foods were invented, and large-scale technological development enabled mechanised and automated commercial precision cropping. In recent times, retail market demand has returned for unshelled podded peas – a manually picked crop known colloquially as ‘pulling peas’.

How to grow peas

Seeds can be sown directly (illustration 1) or transplants (illustration 2) can be raised under protection, giving an early boost for growth and maturity. Peas are cool season crops. They grow best at 13-18°C and mature about 60 days after sowing.

Illustration 2: Pea seedlings | Image credit: Geoff Dixon

Some cultivars such as Meteor can be grown over winter, preferably protected with cloches for very early cropping. The spring sown The Sutton cultivar group (CV) gives rapid but modest returns, and main crop CVs, such as Hurst Green Shaft, deliver the heaviest returns (illustration 2). This cultivar forms several long, well-filled pods at the fruiting nodes.

Sugar peas or mange tout – where the entire immature pod is eaten – is a popular fresh crop, while quick-growing pea shoots that mature in 20 days from sowing are excellent additions for salads or as garnishes for warm cuisine.

Human health benefits significantly by including peas in the diet. As well as being an excellent protein source, they produce a range of vitamins and nutrient elements. Their coumestrol content aids the control of blood sugar levels, helping combat diabetes, heart diseases and arthritis.

So, it’s certainly worth finding a spot for this versatile vegetable in your garden.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science.

The iris family (Iridaceae) provides gardeners with a glorious array of colourful and frequently well scented flowers. Originating from both tropical and temperate regions, some such as freesias are best cultivated under protection. Others such as gladioli and crocus are reliable garden plants.

Iris, or fleur-de-lis, is one of the larger genera, offering colour and interest from the very earliest springtime through to May and June. The earliest and always most welcome is Iris unguicularis (previously Iris stylosa). Flowers (see illustration 1) emerge in the darkest days of December, encouraged by the warming effects of climate change.

Illustration 1: Iris unguicularis (syn Iris stylosa) / Image credit: Geoff Dixon

Originating from North Africa, it thrives in south facing dry borders, preferably under a wall where winter sunshine encourages proliferous flowering. Every few years, lift and divide the clump of small rhizomes after flowering has finished. Remove older growth and replant younger roots with a modest handful of compost and water well. Established clumps can be cut back, removing dead leaves during late spring.

By contrast Iris pseudacorus, the water flag, thrives in wet, boggy places or even when immersed in water. Found across Europe, it is a British native plant producing vivid yellow flowers that are rich sources of nectar. In parts of Scotland it forms large expanses of natural growth that are favoured by nesting corncrakes. It can be cultivated as part of water purification programmes since nitrogen and phosphorus are extracted by the vigorous root systems.

Illustration 2: Iris germanica / Image credit: Geoff Dixon

The prima donna is Iris germanica, the flag or bearded iris. These are stately plants, producing flower spikes up to one metre high and furnished with multicoloured flowers (illustration 2). Upright standard petals can contrast completely with the falls which bear a beard of yellow pollen bearing stamens. Fertiliser should be applied as the flower spikes appear. It should be applied again after flowering, stimulating root growth in anticipation of a colourful display in the next season.

Illustration 3: Rhizome ready for division / Image credit: Geoff Dixon

The rhizome is a large swollen ground-creeping stem from which side shoots develop with a terminal area of older tissue (illustration 3). Every four or five years, the rhizomes should be lifted and divided by removing the terminal tissue and splitting off side shoots with a sharp knife. These and the main rhizome should be replanted carefully, ensuring that they rest on the soil surface with their fibrous roots buried beneath them. Multiplication eventually provides a border filled with very colourful displays that can persist for a month since flowers frequently emerge along most of the spike.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

Perennial bush soft fruits are among the crown jewels of gardening. Gooseberries, red currants and blackcurrants when well established will annually reward with crops of very tasty ripe fruit which provide exceptional health benefits. These bushes will mature into quite sizeable plants so only relatively few, maybe one to five of each will be sufficient for most home gardeners or allotment owners.

Header image: Gooseberries | Image credit: Geoff Dixon

The art of successful establishment lies in initial care and planting. Buy good quality dormant plants from reputable nurseries or garden centres. Plunge the roots deeply in a bucket of water and plant as quickly as possible. These crops need rich fertile soil which is weed free and has recently been dug over with the incorporation of farmyard manure or well-rotted compost. Each bush requires ample growing space with at least a one metre distance within and between rows.

Take out a deep planting hole and soak with water. Place the new bush into the hole, spreading out the root system in all directions. Add mycorrhizal powder around and over the roots, which encourages growth promoting fungi. These colonise the roots, aiding nutrient uptake and protecting from soil borne pathogens. Carefully fold the soil back around the roots, shaking the plant. That settles soil in and around the roots and up to the collar which shows where the plant had grown in the nursery. Tread around the collar to firm the plant and add more water. Normally, planting is completed in late winter to early spring before growth commences.

Redcurrants | Image credit: Geoff Dixon

As buds open in spring, keep the plants well-watered. It is crucially important that the young bushes do not suffer drought stress, especially during the first summer. Supplement watering with occasional applications of liquid feed which contains large concentrations of potassium and phosphate plus micro nutrients. Remove all weeds and flowers in this first year. That concentrates all the products of photosynthesis into root, shoot and leaf formation for future seasons. Clean up around the plants in autumn, removing dead leaves that might harbour disease-causing pathogens.

These plants will flower and fruit from the first establishment year. Each bush will produce fruit which is a succulent and rewarding source of health-promoting vitamins and nutrients.

Blackcurrants | Image credit: Geoff Dixon

Blackcurrants are a fine source of vitamin C and have twice the antioxidant content of blueberries. Redcurrants are sources of flavonoids and vitamin B, while gooseberries are rich in dietary fibre, copper, manganese potassium and vitamins C, B5 and B6.

Blackbirds also like these fruits so netting or cages are needed! Continuing careful husbandry will yield a succession of expanding and rewarding crops.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

Variously known as zucchini, courgette, baby marrows and summer squash, this frost tender crop is a valuable addition for gardens and allotments. Originating in warm temperate America, the true zucchini was developed by Milanese gardeners in the 19th century and popularised in the UK by travellers in Italy. It quickly matures in 45 to 50 days from planting out in open ground by early May in the south and a couple of weeks later farther north.

Alternatively, use cloches as frost protection for early crops. Earliness is also achieved by sowing seed in pots of openly draining compost by mid-April in a greenhouse or cold frame. Courgettes have large, energy-filled seeds. Consequently, germination and subsequent growth are rapid.

Sow seed singly in 10cm diameter pots and plant out when the first 2-3 leaves are expanding (illustration number 1). Alternatively, garden centres supply transplants. These should be inspected carefully, avoiding those with yellowing leaves or wilting foliage. Each plant should have white healthy-looking roots without browning.

Illustration 1: Courgette seedlings germinated in a greenhouse.

Courgettes grow vigorously and each plant should be allocated at least 1 metre spacing within and between rows. They require copious watering and feeding with a balanced fertiliser containing equal quantities of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium.

Botanically, they are dioecious plants, having separate male and female flowers, (illustration number 2). They are beloved by bees, hence supporting biodiversity in the garden. Slugs are their main pest, causing browsing wounds on courgette fruits; mature late-season foliage is usually infected by powdery mildew fungi that cause little harm.

Illustration 2: Bee-friendly (and tasty) courgette flower.

Quick maturing succulent courgettes are hybrid cultivars, producing harvestable 15-25 cm long fruit (berries) before the seeds begin forming (illustration number 3). Harvest regularly at weekly intervals before the skins (epicarps) begin strengthening and toughening. Skin colour varies with different cultivars from deep green to golden yellow. The choice rests on gardeners’ preferences.

Courgettes are classed and cooked as vegetables and their dietary value is retained by steaming thinly sliced fruits. Courgettes are a low-energy food but contain useful amounts of folate, potassium and vitamin A (retinol). The latter boosts immune systems, helping defend against illness and infection and increasing respiratory efficiency. Eyesight is also protected by increasing vision in low light.

Illustration 3: Courgette fruit ready for the table.

Courgettes are, therefore, valuable dietary additions year-round. Courgette flowers are bonuses, used as garnishes or dipped in batter as fritters or tempura. Overall, the courgette is a most useful plant that provides successional cropping using ground vacated by over-wintered vegetables such as cabbage, Brussels sprouts or leeks.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

Broad beans are an undemanding and valuable crop for all gardens. Probably originating in the Eastern Mediterranean and grown domestically since about 6,000BC, this plant was brought to Great Britain by the Romans.

Header image: a rich harvest of succulent broad beans for the table

Capable of tolerating most soil types and temperatures they provide successional fresh pickings from June to September. Early crops are grown from over-wintered sowings of cv Aquadulce. They are traditionally sown on All Souls Day on 2 November but milder autumns now cause too rapid germination and extension growth. Sowing is best now delayed until well into December. Juicy young broad bean seedlings offer pigeons a tasty winter snack, consequently protection with cloches or netting is vital insurance.

From late February onwards dwarf cultivars such as The Sutton or the more vigorous longer podded Meteor Vroma are used. Early cropping is promoted by growing the first batches of seedlings under protection in a glasshouse. Germinate the seed in propagating compost and grow the resultant seedlings until they have formed three to four prominent leaflets. Plant out into fertile, well-cultivated soil and protect with string or netting frameworks supported with bamboo canes to discourage bird damage.

Young broad bean plants supported by string and bamboo canes

More supporting layers will be required as the plants grow and mature. Later sowings are made directly into the vegetable garden. As the plants begin flowering remove the apical buds and about two to three leaves. This deters invasions by the black bean aphid (Aphis fabae). Winged aphids detect the lighter green of upper foliage of broad beans and navigate towards them!

Allow the pods ample time for swelling and the development of bean seeds of up to 2cm diameter before picking. Beware, however, of over-mature beans since these are flavourless and lack succulence. Broad beans have multiple benefits in the garden and for our diets. They are legumes and hence the roots enter mutually beneficial relationships with nitrogen fixing bacteria. These bacteria are naturally present in most soils. They capture atmospheric nitrogen, converting it into nitrates which the plant utilises for growth. In return, the bacteria gain sources of carbohydrates from photosynthesis.

Broad bean root carrying nodules formed around colonies of nitrogen fixing bacteria

Broad beans are pollinated by bees and other beneficial insects. They are good sources of pollen and nectar, encouraging biodiversity in the garden. Nutritionally, beans are high in protein, fibre, folate, Vitamin B and minerals such as manganese, phosphorus, magnesium and iron, therefore cultivating healthy living. Finally, they form extensive roots, improving soil structure, drainage and reserves of organic nitrogen. Truly gardeners’ friends!

Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science (ISBN 978-1-138-20906-0) published by Routledge 2019.

Gardens and parks provide visual evidence of climate change. Regular observation shows us that our flowering bulbous plants are emerging, growing and flowering. Great Britain is particularly rich in long term recordings of dates of budbreak, growth and flowering of trees, shrubs and perennial herbaceous plants. Until recently, this was dismissed as ‘stamp collecting by Victorian ladies and clerics’.

The science of phenology now provides vital evidence that quantifies the scale and rapidity of climate change. Serious scientific evidence of the impact of climate change comes, for example, from an analysis of 29,500 phenological datasets. This research shows that plants and animals are responding consistently to temperature change with earlier blooming, leaf unfurling, flowering and migration. This scale of change has not been seen on Earth for the past three quarters of a million years. And this time it is happening with increased rapidity and is caused by the activities of a single species – US – humans!

Iris unguicularis (stylosa).

Changing seasonal cycles seriously affects our gardens. Fruit trees bloom earlier than previously and are potentially out of synchrony with pollinators. That results in irregular, poor fruit set and low yields. Climate change is causing increased variability in weather events. This is particularly damaging when short, very sharp periods of freezing weather coincide with precious bud bursts and shoot growth. Many early flowering trees and shrubs are incapable of replacing damaged buds, as a result a whole season’s worth of growth is lost. Damaged buds and shoots are more easily invaded by fungi which cause diseases such as dieback and rotting. Eventually valuable feature plants fail, damaging the garden’s benefits for enjoyment and relaxation.

Plant diseases caused by fungi and bacteria benefit from our increasingly milder, damper winters. Previously, cooling temperatures in the autumn and winter frosts prevented these microbes from over-wintering. Now they are surviving and thriving in the warmer conditions. This is especially the case with soil borne microbes such as those which cause clubroot of brassicas and white rot, which affects a wide range of garden crops.

Hazel (Coryllus spp.) typical wind-pollinated yellow male catkins, which produce pollen.

Can gardeners help mitigate climate change? Of course! Grow flowering plants which are bee friendly; minimise using chemical controls; ban bonfires – which are excellent sources of CO2; establish wildlife-friendly areas filled with native plants and pieces of rotting wood, and it is amazing how quickly beneficial insects, slow worms and voles will populate your garden.

—

Professor Geoff Dixon is the author of Garden Practices and their Science, published by Routledge 2019.